It’s a funny thing, finding out you’re a lamplighter.

Apparently, we’ve all been trudging through the evening streets of an 1890s London, tending our gas lamps, watching from afar as the new electric ones flicker into existence. One by one they render us redundant. A change, we are told, we will eventually be thankful for.

For as The New York Times recently noted:

Unemployment for recent college graduates has jumped to an unusually high 5.8 percent in recent months… unemployment for recent graduates was heavily concentrated in technical fields like finance and computer science, where AI has made faster gains.

In a recent Axios article warning of a “job bloodbath,” Dario Amodei, CEO of Anthropic, said that 50% of entry-level white-collar positions could be eliminated in under five years, and predicts that overall unemployment will spike to 10-20%.

Some say this is hype. But it’s not all hype. How slow will it really go? How fast? Nobody knows.

Of course, some people think they have The Special Job, and no matter how advanced AI gets, they therefore don’t need to worry. E.g., Marc Andreessen, a venture capitalist investing heavily in automating away white-collar work, apparently has The Special Job, musing about being a venture capitalist that:

So, it is possible—I don’t want to be definitive—but it’s possible that [investing in start-ups] is quite literally timeless. And when the AIs are doing everything else, that may be one of the last remaining fields…

Unfortunately, the rest of us are mere lamplighters. That isn’t my analogy, by the way; it’s Sam Altman’s, the CEO of OpenAI. And what a waste of time, he bemoans, the job of the lamplighter was. How happy they would be to witness their own extinction, if only they could see the glorious future. As Altman describes it in his blog post, “The Intelligence Age:”

… nobody is looking back at the past, wishing they were a lamplighter. If a lamplighter could see the world today, he would think the prosperity all around him was unimaginable.

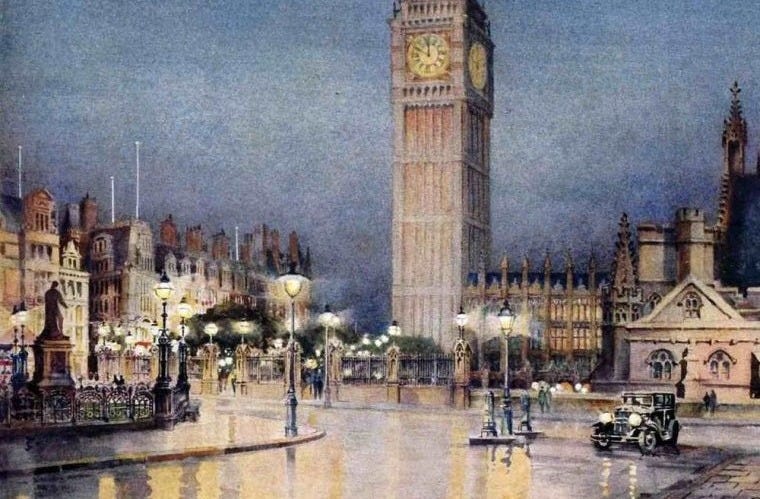

Altman has made this analogy in interviews and talks as well, but as it turns out, his repeated reference to lamplighters as a job happily lost is, historically, a particularly bad one. Before cities like London, Paris, and New York switched over to electricity, the job of being a lamplighter had already been much romanticized. Charles Dickens wrote a play, The Lamplighter, which he later adapted into a short story, and there was the 1854 bestselling novel The Lamplighter by Maria Susanna Cummins, in which the young girl protagonist is rescued by a lamplighter literally named “Trueman Flint.” So beloved was the profession that parents taught their children to declare “God bless the lamplighter!”

In his editorial, “A Plea for Gas Lamps,” Robert Louis Stevenson (of Treasure Island fame) laments firsthand the lamplighter’s replacement with electricity:

When gas first spread along a city… a new age had begun for sociality and corporate pleasure-seeking... The work of Prometheus had advanced another stride…. The city-folks had stars of their own; biddable domesticated stars…

The lamplighters took to their heels every evening, and ran with a good heart. It was pretty to see man thus emulating the punctuality of heaven's orbs…people commended his zeal in a proverb, and taught their children to say, “God bless the lamplighter!”…

A new sort of urban star now shines nightly. Horrible, unearthly, obnoxious to the human eye; a lamp for a nightmare! Such a light as this should shine only on murders and public crime, or along the corridors of lunatic asylums. A horror to heighten horror. To look at it only once is to fall in love with gas, which gives a warm domestic radiance fit to eat by. Mankind, you would have thought, might have remained content with what Prometheus stole for them and not gone fishing the profound heaven with kites to catch and domesticate the wildfire of the storm.

Is this true? Have we, without knowing it, lived under lights fit only for murderers and the insane? After all, gas burning resembles “biddable domesticated stars,” or a campfire. And what does sunlight and firelight mean to us humans, psychologically? It often means safety. Yet in the march of progress to illuminate our streets and our homes, we replaced the light of the sun with the light of the storm. And what do a storm and its arcs of electricity mean, psychologically? Danger.

And so it goes. Every night I drive, I think: These headlights are too bright, too cold, too technological. I miss the softer hues of my youth, when yellow cones swept the roads and traced paths across my bedroom walls before I slept.

The colors and lights of our civilization, precisely because they are so low stakes, demonstrate that nothing is gained for free in progress. It is a microcosm, and so Stevenson’s words about lamplighters have a chilling edge in the AI age:

Now, like all heroic tasks, his labours draw towards apotheosis, and in the light of victory he himself shall disappear.